Essential Notes on Linguistics, 9

A Guided Tour into MetaEnglish

It is no surprise to me to hear that readers have trouble reading my poetry, written as it is in MetaEnglish, which I fondly call Steevtok (aka Steevspeek, Steevspel). Not only is MetaEnglish written phonetically, thus changing the appearance of most words, but it uses new and much more flexible rules of grammar than standard English (which I call Old English). And, I don’t hesitate to create new words or borrow foreign words, as well.

This makes it impossible to read my work quickly and easily. Studies strongly suggest that we decipher words like hieroglyphs, seeing the whole word as a unit and gauging the context, and only when uncertain, processing consciously the individual letters. Thus, when you read my poetry, you can’t fall back on your default reading method of roaring along at 90 mph and not being concerned with most of the scenery. Until you become fluent in MetaEnglish, you will need to sound out many words from the individual letters. And even after you gain some fluency, you will still need to drive in first gear, being prepared to stop, back up, and, horror of horrors, reread, possibly numerous times. The rest of this essay will unpack my thinking as I write in Steevtok. I hope you will find it a useful guided tour, which I will end with a brief discussion about why I have chosen to hold to this difficult course, and why I believe there is much to be gained if you are prepared to accept the rules of the road in Steevtok country.

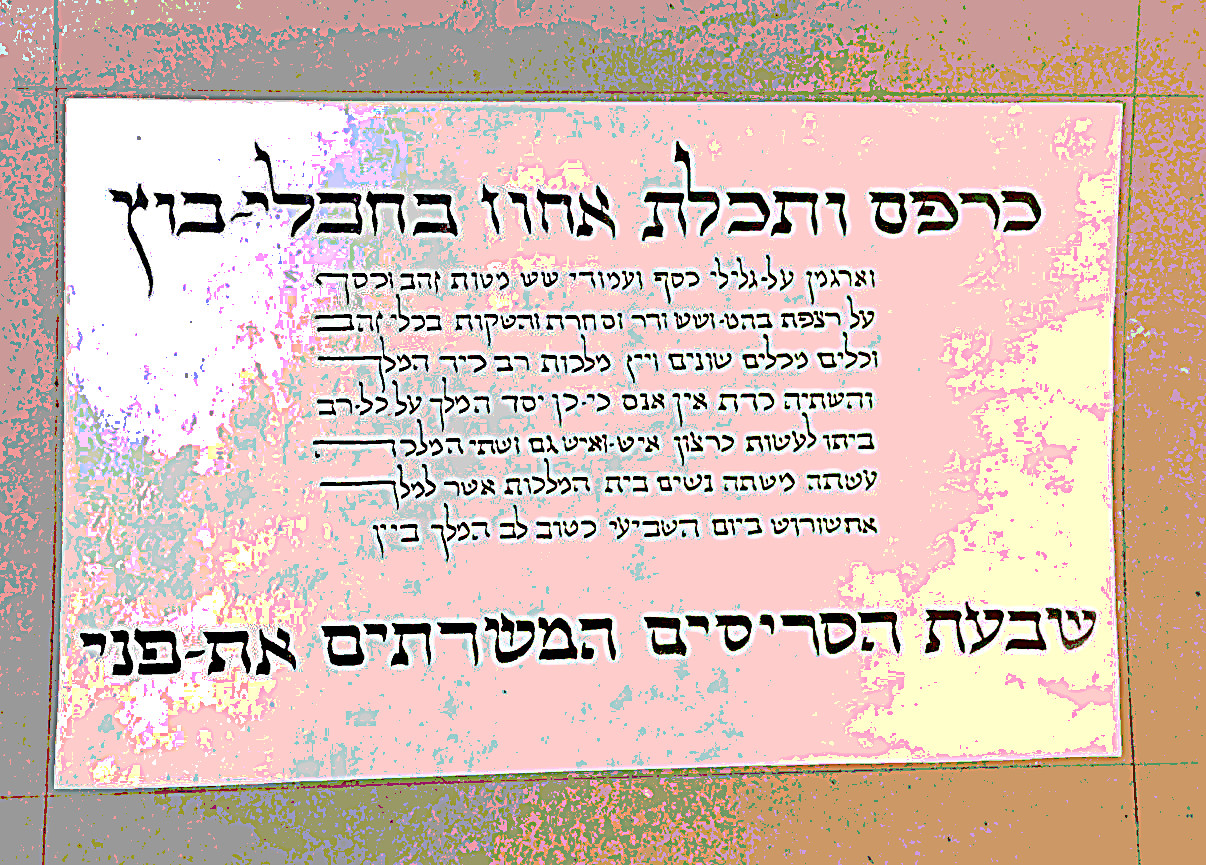

I will focus on just a few lines from Wile Sayenz the Sh'ma, I Wuz Herd..., which I translated into Old English as While Saying the Sh'ma, I Heard.... I’ll compare the 2 versions, and explain what had to be stripped out of the Steevtok version to make it conform to Old English.

First, let’s look at the title. I’ve talked about the verb form embodied in “sayenz” elsewhere - a combination verb and noun, ‘saying’ and ‘sayence’ (no, it’s not a word in use in Old English, tho the form is common; it’s a word/form I’m adding to the language), as well as a standardization of the slang/spoken form, sayin’, thus endorsing the organic, ever-changing nature of language. All of that information and superimposed thinking is lost in “Saying”.

The translation, “I Wuz Herd” to “I Heard” involves a similar stripping of information embedded in MetaEnglish to conform the text to Old English. In this case, the verb “Wuz” plays a number of active roles. First, it can be read as making my hearing a more passive experience, slightly removed from the more direct, “I heard”. Second, it pushes the experience out of the present into the past, making it more reflective. Third, it flips the experience from me doing the hearing, to me being heard. Consider the context: Here I am, praying, attempting to make myself present/heard in the divine/infinite/eternal realms. At the same time, the prayer I am reciting demands that I listen for/to the divine. Thus “Wuz Herd” superimposes my attempt to listen with my actual hearing. And of course, the whole point of this poem is to let the reader know that it is possible to hear/experience the divine, while giving the reader the specific tools that may facilitate that very hearing. My interest in writing this poem is not so much to tell you what I saw, but to help you, the reader, have your own transcendental experience. I am trying to heighten your experience by expanding and amplifying the neural processing of your brain, by showing you more than one thing at the same time, by challenging you to read with more open eyes, with more expansive thinking. I should note that the word “Herd” will also generate ‘after images’, ‘shadows’ that will color your thinking subtly, in this case with the idea of ‘a herd’ (of animals).

An aside, before I penetrate further into the structure of MetaEnglish:

I use the term “divine” with some trepidation. It is a word that carries a lot of baggage, much of it useless or detrimental. Thus, in my first reference to this word I combined it with “infinite” and “eternal”. I ask you to imagine experiencing the world with infinite consciousness, a consciousness that transcends time and space. That, for me, is the “divine.” I am not talking about some childish understanding of a God that is more like Santa Claus -- that fellow up in the sky who brings gifts to good little boys and girls and makes bad little boys and girls feel bad. However, if you really don’t like the word “divine” please replace it with “infinite” or “eternal” or some other word you prefer that conveys the sense of a state of awareness that is vastly more expansive, insightful, and compassionate than your normal state of consciousness.

The first line of the poem is,“Yur evver wun iz this Ruwakh werl”, which I translate into, “You are in everyone in this Ruach world.” The translation states a commonly held opinion that is probably more cliche than insight, even tho, in those moments when one experiences the divine, it is no cliche at all, but a great astonishment and elevation. But the MetaEnglish version presents a very different statement. Here, multiple things are being said at once, some of which are well outside our standard theology and well-trod imaginings. If I am referring to the divine with the word “Yur”, then, beyond the translation into Old English, I am trying to say: 1. You ARE everyone; tho blind, we are coequal with the divine; 2. You are ever, always, one, unified, and that is the essence of Ruach/Spirit; 3. the sum of everyone is the Spirit; 4. the Ruach, the Spirit is a separate world; 5. the Ruach is this world, and NOT a separate world. By breaking the rules of spelling and grammar, I create a translucency that is not possible in standard English. Rather than an opaque wall of words (brick-like words), I am trying to create a window of words (translucent words), a window into multiple dimensions; or, words as prisms that diffract light into multiple colors.

The first sentence of the second stanza is:

Yu wuz a spoke in a roer

That ar the seemz a silens,

Tho yur proffets sayenz ar wisperz

Evver wun heerz

But hu ar lissenz?

I translate this into:

You who spoke in a roar that seemed like a silence, tho Your Prophets say it is a whisper everyone hears, but who is listening?

Here again, the translation tells a story well within the framework of what a well-read reader would know. I hope it is succinct and penetrating, but I expect it is not a revelation. The Steevtok version aspires to much more. “Yu wuz a spoke in a roer...” sets the tone with its noun-verb fusion in ‘spoke’. Obliquely referencing Ezekiel’s “wheel in a wheel”, the divine is described as having once been a spoke of a roar, but not all of the roar. In other words, the divine is embedded in reality, but not so easily extracted. At the same time, the line allows for a reading in which the divine did speak in a roar. This is set in the past tense.

The next line, however, “That ar the seemz a silens” modifies the first, and is set in the present tense. What was once hearable (theoretically) now seems to be silent, or it is embedded in the seams of silence, the sounds of silence, or it is lost in those seams. Note also the double meaning of ‘a’ in “seemz a silens,” acting as an article and also as the preposition, ‘of’. This is another example of how I integrate slang, organic grammar, into MetaEnglish.

The third line modifies yet again our understanding of, or our expectations of what the experience of divine hearing will be like: “Tho yur proffets sayenz ar wisperz”. The prophets have said they heard it as a whisper, or the prophets’ words themselves are but whispers. “Evver wun heerz // But hu ar lissenz.” Everyone hears the prophets’ words, or is it, everyone hears the divine voice in the seams of our silences? But, indeed, who is listening, and who can hear what is silent? Note, also the verb-noun fusion of “lissenz.” As a verb it can mean, ‘who are listeners’, but as a noun it becomes something more subtle and rare than that: who is it that defines themselves by their listening? Who is the embodiment of listening? It is one thing to listen; it is another thing entirely to be A Listener, a medium for the divine.

I believe that brief tour has touched on many of the ways I use MetaEnglish to try to expand awareness and enrich our language and our thinking. To summarize, the core concepts of MetaEnglish are:

1. a normalization of the written to the spoken word;

2. translucency of language;

3. superimposition of words, grammatical forms, images, time frames, and ideas;

These 3 for the sake of:

4. attempting to create higher dimensionality and richer complexity in our thinking; and

5. attempting to replicate, or generate, the experience of the divine.

If this makes sense to you, or if you find it intriguing, I invite you to read my works. You might want to begin with the earlier writings, In the Harvest ov Nations or the Elmallah series. After that The Pardaes Dokkumen is intended to be a new book of Zohar. Beyond that, my current project is The Atternen Juez Talen, 2000 years of the Eternal Jew’s journeys and experiences. And of course, I urge you not just to read these books, but to extend the process yourself! Steevtok is an innovation opening up new potential in the technology of language.